What is a "Reason"?

an objective explanation for a truth

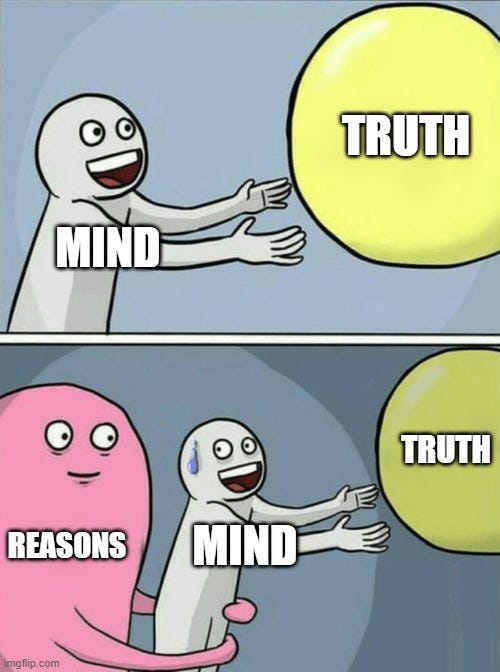

To understand why the PSR is self-evident and why its criticisms are self-defeating, we need to understand precisely what "reasons" are. Many have one of the misconceptions that "reason" is just a subjective value judgment, a useful tool of manipulation, or just another debate tactic. It's nothing more than a piece of personal equipment whose value is judged on its practicality.

These types of views are horrendously misguided and prevent us from recognizing the PSR's blatant self-evidence. This post seeks to correct these views by first positing a definition of "reason.” You can interpret the below as my reasons for "reason."

A "reason" is an objective explanation for something. "Objective" here means a mind-independent, universally comprehensible thought (see here for a discussion on objective thoughts).

And "explanation" means a ground for a truth—an explanation must solve a mystery, shed light on darkness, make what was opaque transparent, and familiarize us with the unfamiliar. Whatever ever other metaphor you have for “make more clear” is perfectly acceptable.

When you discover an explanation, you comprehend what before you felt was incomprehensible. You see things in a way that makes sense. And when an explanation is "objective," anyone can similarly see this way. As an analogy, an "objective explanation" is like a set of glasses that not only lets you see things more clearly but that you can give to anyone else to wear for them to see the same. And its best feature is that you can still keep the glasses you're wearing even after letting someone else wear them. We can keep on giving out these “reason” glasses to one another to make truth clearer.

Simply put, a "reason" is a way to understand, that anyone could understand.

Congratulations if you have fully understood what I mean, in which case you may stop reading here. But for those who need further convincing in order to wear this set of glasses on the definition of “reasons”, see the more detailed explanation below, along with the "comment" button, to have any questions addressed.

Can “Reason” be Defined?

Some have doubted whether there is a central concept in the term "reasons", and if not, they may take either a primitivist (basic fact) or pluralistic view (“reasons” can have separate definitions).1 A "reason" may, therefore, mean entirely different things in either the epistemic, normative, or scientific domains. Philosophers have tended to retreat into a "family resemblance" view of reasons because of how far-reaching and seemingly unconnected the different uses of “reasons” are.

However, "reason" is too foundational of a concept for such a pathetically half-assed and cowardly answer. We rightly demand precision. "Knowledge" supposedly lacked a universally applicable conceptual condition, yet one exists (notwithstanding Gettier problems). The same is true of “reasons,” which is also definable. Once we sufficiently grasp "reasons," we will be better equipped to understand how the PSR is a fourth law of thought.

This article will offer a universally applicable core concept of a "reason,"—that of an "objective explanation." Each of the “objectivity” and “explanation” requirements are defended below.

Objectivity

Philosophers in different fields of study have distinguished “objective reasons” from “subjective reasons.” They would consider the former as holding mind-independent significance, whereas the latter would only be mind-dependent.2 Some reasons are universal, whereas others are just personal, as some philosophers have discovered in their own field, like normativity, epistemology, and logic.

However, because different domains of philosophy have different conceptions of what constitutes "reasons," philosophers falsely assume that “reasons” are purely contextual, lacking any unifying core concept. We can show how this “subjective” vs. “objective” delineation can be generalized to “reasons” generally.

As I've argued, what makes a thought objective is that it is a mental product that can be universally communicated and comprehended, at least in principle. A mute person can, of course, still have thoughts, and they could communicate them in principle; they just happen to not express them. Our thoughts aren't any less "thought-like," because we keep them in our heads. It doesn’t matter whether some worldly restriction prevents a thought from being communicated (like a vow of silence, disability, or personal preference). So long as we can convey our personal ideas to others, in principle, that idea is an "objective thought."

For a “thought” to be “objective,” it must be universally comprehensible. To illustrate with a metaphor, to be able to have a conversation, we need to throw thoughts to our partner and catch thoughts when our partner throws thoughts back. If we don’t understand our partner, we ask for clarification or to rephrase in order to properly grasp their thoughts and logically follow up with our own. If "thoughts" were only subjective, then they would be only "ideas,"—stuck in the mind and impossible to transmit.3

Subjective ideas include first-person experiences, personal memories, and private ideas that we cannot share with others. Meanwhile, objective thoughts consist of all concepts we can express through symbolic representation, like language and mathematics. We can't transfer everything in our heads to someone else's, but we can communicate the ones we can transfer using the representational systems of language and logic.

To tell whether a mental entity is objective or subjective, we would need to know whether that “thought” is universally comprehensible or only personal.

For example, the chair I'm sitting on can be sat on by anyone, which is why it’s an "objective" chair. Yet if I had a "chair" that only I could see and feel (for example, I was a mime and sat on an imaginary chair whose boundaries I determined myself), then that chair would be a "subjective chair." The former chair is mind-independent, and the latter chair is mind-dependent.

The same applies to thoughts. If any “reasonable person” could understand a certain thought, then that thought would be objective. However, if I had a "thought" that only I could have and couldn’t communicate to others, such a mental entity could only ever be an "idea.”

But, what does "reasonable person" mean exactly? In the legal setting, if a law were to adopt an “objective standard” for judging a person's actions, it would adopt what is known as the "reasonable person" standard. This standard requires that a court examine what a “reasonable person” would do under similar circumstances, regardless of any personal facts about the actual person in question.

This is opposed to a "subjective" standard, which would take a holistic view of one's personal facts and relevant circumstances.

A "reasonable person" is informed by objective reasons anyone could grasp. Meanwhile, a “subjective standard” looks at what reasons each of us personally grasps, focusing on our unique personalities and the actual facts.

As with the "reasonable person" standard, which our legal system relies on, whether a "reason" is objective can be measured against whether a "reasonable person" could understand it or whether its comprehension would be contingent on one's personal attributes and background beliefs.

For example, if I was talking about the Sears Tower, I could never convey my personal memories and experience to any "reasonable person," about the Sears Tower. However, I can still give the "reasonable person" objective thoughts about the Sears Tower, such as facts about its location, interior, and height. These thoughts may be true or false based on whether they correspond with reality. But a wrong thought is still a thought. We're only able to judge a thought because we can understand it and determine whether it matches up with reality or not.

If you want a hard image, whatever I can and cannot convey to a "reasonable person" can serve as a standard here for what makes a thought "objective,"

We can even be more precise about "what a reasonable person could understand" by creating a rule that any "objective thought" must obey the "laws of thought."

Laws of Thought

For a thought to exist objectively, it must obey the laws of thought, meaning it must be logically coherent. Nonsense statements like "Colorless green ideas sleep furiously" and "This sentence is false" fail to contain a thought because they contain contradictions. Each of those sentences can mean different things to different people, as they fail to stand for any objective concept.

Once you have a contradiction, you don't have an objective thought, for no one can understand a true contradiction.

A "square circle" can mean different things to different people, making its meaning truly subjective. "Square circle" is a meaningless symbol, and whatever meaning that term can possess could only exist in someone's head in their own "private language."

Meanwhile, terms like "red circle" or "blue square" are comprehensible, since any reasonable person could comprehend them. They exist in our "public language.”

Now that I hope we understand "objective," let's explain "explanation.”

Explanation

An explanation is a ground of a truth. "Truths" themselves derive from explanations. In philosophy, we don't accept a proposition as true if we don't have an explanation for its truth. We don't go handing out truth cards to propositions, they need to earn it through an objectively acceptable explanation (i.e, a “reason”). So, to the extent you'd like to accept truths, you need to also have their explanation.4 “Explanations” are like a proposition’s ticket into the “set of all true statements.” Accepting a truth without explanation is arbitrary, and “arbitrary” is the only crime a philosopher can charge anyone of.

This broad "explanation" requirement can apply to all domains of truth: physical, metaphysical, mathematical, causal, psychological, social, etc. Every domain that has truths also has explanations. If a domain has only truths without explanations, we would dismiss that domain as ungrounded.

For an explanation to be an explanation, it should remove a mystery about a truth, resolving a puzzle of the explanandum.5 Other metaphors might help. An explanation must shed light, lift the fog, resolve confusion, unlock a secret, peel back a layer, or answer a riddle. Fundamentally, an explanation must create order out of chaos—the entire purpose of philosophy. Our minds cannot grasp truth directly, but we can discover reasons. And from reasons derive truth.

Because explanations ground truths, they exist objectively. Yet, we cannot see or touch these "explanations." But while philosophers have largely accepted the "explanation"-based property of "reasons," they have largely overlooked the need for "reasons" to be objective. We don't understand pure explanations out there in the world. We can only understand them through thought. This is where the "objective" requirement matters for defining “reasons.”

"Explanations" are packaged into thoughts, often in the form of a digestible metaphor (like this one), and conveyed to other minds through language. Although explanations aren't necessarily "thoughts," we can still contain and structure explanations within thoughts to make them universally digestible, and therefore objective.

Furthermore, we can only judge explanations as true or false if we first understand them. An explanation can't just exist in our heads; it needs to be comprehensible to others so that they can also test their truth. And we can only understand explanations that are in the form of thoughts. If an "explanation" is incomprehensible as a thought (like by violating the laws of thought through the existence of a contradiction), then the explanation would be meaningless. Thoughts need to be presentable in a “meeting of the minds.”

For example, take the contradictory explanation: “The plant is growing because it is in complete darkness, and plants only grow in the sunlight.” This can’t be an explanation since it is also a contradiction. This statement would only serve to confuse your interlocutor and they wouldn’t understand it in a “meeting of the minds.”

If the above isn't clear enough, we can use a simple test. Is it an explanation that only a person with specific prejudices and personal biases can understand and accept? If so, it is a subjective reason.

Is it instead an explanation that any reasonable person can understand and accept, regardless of such subjective prejudices and biases? If so, then it is an objective reason.

Under this framework, the supposed "reasons" we give can be right, wrong, or incomprehensible, depending on whether the explanation is connected to reality and whether the thought itself is coherent.

A "reason" must therefore both be "objective" and an "explanation" for it to a reason. The reason could be right or wrong, but those are the only two requirements it must satisfy to count as a reason.

Conclusion

A “Reason” is an objective explanation.

"Objective" means mind-independent, which, as applied to a “reason”, means whatever thought that is created and conveyable by the mind (i.e., obeys the laws of thought and which any reasonable person could understand).

"Explanation" means a ground for a truth. To the extent a truth is grounded on anything, that ground must be an explanation.

“Objective explanations" are, therefore, conveyable thoughts whose contents are the grounds of a truth.

See Wedgwood, Ralph. The Value of Rationality. Oxford University Press, 2017. Chapter 4. Wedgwood provides an overview of different conceptions of “reasons,” and critiques the “Reason First” view that there is a central concept of “reasons” that grounds its many uses. This article adopts a “Reason First” view.

For example, in the realm of morality, see Parfit, Derek. On What Matters, Volume 1. Oxford University Press, 2011, pp. 40–44. Parfit delineates between "objective reasons" and "subjective reasons," which exist as agents independently and agents dependently, respectively. Also, see Korsgaard, Christine M. The Sources of Normativity. Cambridge University Press, 1996, pp. 134–138. Korsgaard similarly distinguishes “private” and “public reasons”, and provides a criteria of universalizability for the latter. In epistemology, see the general distinction between doxastic and propositional justification, delineating beliefs that rely on objective and subjective reasons respectively, discussed here.

See Pickard, Dean. "Frege's Concept of the Thought: Necessity, Absolutism, and Transcendental Arguments." PhilArchive, 2023, https://philarchive.org/archive/DEAFCO. Pickard explains the difference between objective Fregean “senses” and subjective “ideas.”

See Brunero, John. 2014. "Reasons, Evidence, and Explanations." In The Oxford Handbook of Reasons and Normativity, edited by D. P. G., 297–318. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Brunero provides an overview of the “reasons as explanation” approach, linked here.

See Pruss, Alexander R. The Principle of Sufficient Reason: A Reassessment. Cambridge University Press, 2006, p. 17.

I'm not sure I think thoughts must be "logically coherent", but this may be a terminology dispute, as I take your point about objectivity. My sense is that a contradiction is still a thought, just not a factual, logical, or coherent one. Yet such "thoughts" seem easily accessible to us as humor or metaphor. A great old song lyric goes, "It rained all night the day I left, the weather it was dry. The sun so hot I froze to death; Susanna, don’t you cry."

Certainly, *explanations* must be factual and logical, though. Ultimately, there should be a coherent framework supporting things all the way down to one's axioms. Perhaps it amounts to needing a different word than "thoughts" here.

Hey, my nerdness loved it, although the prose is a bit of a speed bump for those of us whose day job is not philosophy. But, I guess the audience you have in mind are more familiar with this kind of prose.

I think I am looking at reason from a very different angle than yours, so I need to reread it to be able to elaborate on what I agree with and what I don't and why.