What is a Belief (Part 2: Language, Truth, and Logic)

a belief is definitely giving the property "true" to a proposition

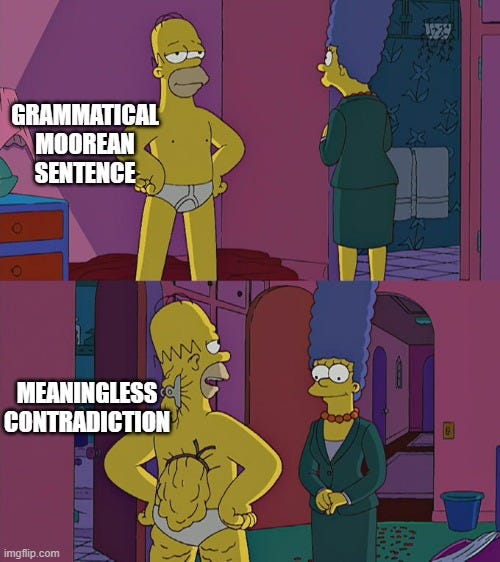

A belief is an attribution of “truth” to a thought. I defended this definition in a prior article and used it to show how “Moorean Sentences” are meaningless. Here, I aim to clarify the idea further and address common criticisms and misunderstandings with this definition.

First, we need to understand the nature of language, particularly the difference between semantics and pragmatics. The abstract definition of “belief” and its specific uses are not the same, but the abstract definition of “belief” determines what “belief” means in every context.

Next, we’ll look at what it means to say something is “true.” A common misunderstanding is that saying something is true means referring to something in the objective world. But the objective world is true without us saying that it is. Attributing truth to truth is redundant.

Statements of fact do not refer to reality. In language, we don’t claim that certain facts are true. The facts of the world are true without anyone else saying so. Statements would be completely useless if they were directed to the world.

Rather, our truth claims are directed at propositions (or thoughts). By believing certain propositions, we give them the property of “true.” And these propositions are only objectively true or false depending on how they happen to correspond with reality. When we say what is true corresponds to the world, we understand that there is a difference between propositions that can have the property of “true” and the world itself.

Last, we’ll look at the nature of logic to fully appreciate why Moorean Sentences (ex: “It is raining. I do not believe that it is raining”) are nonsense. Like the Liar’s Sentence, Moorean Sentences are illogical and are therefore meaningless.

Illogical statements like “This sentence is false” or “This square circle is red and blue all over” can have pragmatic, subjective meanings but not semantic, objective meanings. People can interpret these sentences in a way they want. And I’m sure people can attribute different meanings to nonsensical statements.

However, the fact that people interpret these illogical sentences differently is exactly why these statements lack objective meaning. When there is no shared ground, people make up their own ground. Moreover, everyone thinks their own interpretation of illogical statements is *the true* meaning. And you wouldn’t be able to prove them wrong, because nonsense sentences don’t have an objective meaning.

All objective thoughts must be logical. A thought that isn’t logical isn’t a thought at all. So, our sentences must be rational to convey meaning. If statements were illogical, no one would truly know what something means. Take the sentence “This sentence is false.” Because this sentence is logically incoherent, it has no objective meaning. And because it has no objective meaning, people give it whatever meaning they want—i.e., subjective meaning. Since it is subjective, it has no mind-independent truth.

Without logic, there is no objective meaning. And without objective meaning, there is nothing we can direct our truth claims to.

By understanding the nature of language, truth, and logic, we can comprehend why a “belief” is an attribution of truth to a proposition.

2. Language

As previously argued, language is a tool for conveying thoughts. To transfer thoughts from Abby to Bob, Abby needs to use the language both she and Bob use. Moreover, Abby’s thoughts must be comprehensible; she can’t convey an illogical thought since Bob couldn’t understand it.

But although thoughts must be logical, language doesn’t need to be. Language is pragmatic, not logical. So long as a language can convey a thought, then that language has done its job. You can convey meaning with semantically illogical sentences. Metaphors like “Your silence is deafening” may seem like contradictions but are still comprehensible.

To understand Moore’s Paradox puzzle, it's helpful to distinguish between semantics and pragmatics. Semantics concerns the meanings of individual words and statements. Pragmatics, meanwhile, deals with how meaning is actually expressed when these words and statements are used.

Semantics are the abstract rules, and pragmatics are the real-world application. To oversimplify, semantics is objective and pragmatics is subjective. Our words can mean whatever we want them to mean subjectively and in context, but under the rules of semantics, words have an objective meaning.

This definition of “belief” is about semantics, not pragmatics. We can use the word “belief” however we want in a specific conversation. But in the abstract, the rule is that the word “belief” means an agent attributing truth to a certain thought. The fundamental meaning of “belief” grounds its specific uses.

We can even use the word “belief” in ways that appear to contradict its meaning. "I believe" can signal doubt rather than an assertion. The sentence “I believe that the meeting starts at 3 p.m,” expresses less certainty than the more assertive “The meeting starts at 3 p.m.” But this is a feature of pragmatics. The formal definition of “belief” deals with semantics, which is the attribution of truth.

The sentences “I believe that the meeting starts at 3 p.m.” and “The meeting starts at 3 p.m.” both relate to the attribution of truth to a claim, but they mean different things pragmatically.

The core basis of a “belief” is attributing truth to a proposition. How much truth we attribute to a proposition can vary pragmatically based on the circumstances. As a “belief” is only an attribution of truth, there are no semantic differences between the phrases that begin with “I believe that...” and “I believe to be true that...”.

This is a dull but important point to clarify that a term's definition is not the same as its use.

3. Truth

The common perception of “truth” is that it is something external to the world that is immediately present to us. Our minds are simply presented with “truth” through our sensory systems. It is just assumed that our sensory systems track truth. If it were that simple, it would be easy for us to come to the same conclusions about what the truth is.

In language, our beliefs represent truth—beliefs are an attribute of “truth” onto a thought. Our “beliefs” are not truths themselves. They are propositions that we give the property “true” to.

We do not impose truth on the world. The world is already true, regardless of our beliefs. It doesn’t need us to give it truth, for that would be redundant. We impose truth on “thoughts.” And those “thoughts” can be true or false based on their correspondence to the world. Just keep in mind that the thoughts and the world are separate. Beliefs relate to the former, not the latter.

In short, we impose truth on thoughts through beliefs, and our thoughts are only true if they correspond to reality. We do not make truth. However, we can give the property of “truth” to propositions through our beliefs. But what is the truth? That big question will be explored in the next article.

4. Logic

While language doesn’t always need to be logical, our thoughts do. It is our thoughts, or propositions, that our truth claims are directed at. If a proposition isn’t logical (ex: “This square circle is both red all over and blue all over”), then it can’t be truth-apt.

We can easily understand seemingly illogical sentences like “My day was good and bad” or “We have nothing to fear but fear itself.” At first glance, these may appear contradictory, but pragmatically, they convey coherent ideas, such as “My day had both good and bad moments” or “Our fear itself is the real danger.”

In fact, some of the wisest statements are, on the surface, contradictory, but still carry profound meaning. Phrases like “I know that I know nothing” and “The self is not the self” contain a deeper meaning buried in their paradoxical structure. Zen koans like “What is the sound of one hand clapping,” push us into a different mode of understanding beyond the literal words.

But not all nonsensical statements are deep Zen koans. If we were conversing with someone who kept making contradictory statements (like if we were catching them in a lie), then their use of language would likely be in error. Trying to find deeper meaning in illogical stories would be futile. This is the case with “true contradictions,” statements that are the logical equivalent of “both A and not A.” They wouldn’t be making sense.

Sentences can be illogical, but thoughts can’t be. “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously” may seem logical, but it doesn’t convey a thought. It's semantically and grammatically sensible, but pragmatically meaningless.

While anything can mean anything pragmatically or semantically, “Moorean Statements” are contradictions. If someone were to say, “It is raining, but I do not believe that it is raining,” we’d assume that the person is misspeaking. We certainly wouldn’t spend a century analysing it. It wouldn’t convey any information, neither about one’s subjective mental state nor about the objective state of the world.

People could convey meaning through Moorean Statements by agreeing with others that it has some pre-determined meaning. But that meaning would still have to be something logical, even though the sentence is illogical. If it wasn’t logical, it could never be true.

5. Conclusion

Beliefs are those propositions we’ve assigned as “true.”

This is what a belief fundamentally is, and it would factor into determining its meaning in all its instances. A definition of “belief” is not the same as the uses of the word “belief,” but the definition grounds its usage.

Truth claims are directed at propositions, rather than reality itself. We can give propositions in different degrees of truth under other circumstances. But to have a belief, you need to give a proposition some truth.

And all objective meanings must be logical. An illogical sentence can convey logical thoughts, but an illogical thought is no thought at all, even if expressed by a logical sentence. Language might be contradictory, but meaning never could be.

The next article will go deeper and discuss: What is truth?

My sense is that you're drawing an artificial dichotomy between semantics and what you call pragmatics. To me, both seem about meaning — it seems more a matter of degree than a binary difference. Pragmatics seems just a larger context than the individual words.

We may be having semantic difficulties, though — to wit, how we define "semantics". We agree (?) semantics is about meaning, but I was confused by, "Semantics are the abstract rules, and pragmatics are the real-world application." I don't see semantics as rules but as associations between words and what they refer to. (Syntax is rules.)

Regardless, you seem to be building something here, so I'll just see where you go with it!